In the realm of regulatory compliance, one acronym consistently looms large: CAPA or Corrective and Preventive Action. It resonates with anyone involved in FDA-regulated industries, and no matter how diverse my consulting work may be, CAPA always finds its way back into the spotlight.

While I’m passionate about helping companies enhance their process control, integrate superior quality systems, optimize documentation, and make data-driven decisions through process risk analysis, many companies require substantial assistance with CAPA.

Table of Contents

CAPA’s Evolution

A cursory glance at FDA Warning Letters or industry training offerings underscores CAPA’s paramount importance to the FDA and the regulated industries it oversees. In its current form, CAPA has been a fixture since the formal effective date of the Medical Device Quality System Regulation in 1996.

CAPA has evolved beyond merely a crucial sub-system for addressing unforeseen challenges in product manufacturing. In recent years, it has become the cornerstone of quality systems for most companies, extending its reach beyond medical devices.

This begs the question: What does this transformation imply about the state of control within FDA-regulated industries when a system initially designed for remediation now serves as the linchpin for quality systems?

These implications are a topic for another day. Today, I want to delve into the untold story of CAPA.

Real-World CAPA Problems

I’ve observed a common issue as someone frequently encounters CAPA systems, or more precisely, CAPA procedures masquerading as systems. Many companies, in their zeal to establish a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for CAPA, often convolute the CAPA process with the need for a comprehensive CAPA system encompassing incident identification, analysis, categorization, evaluation, investigation, reporting, and follow-up.

Given the increasing scope of CAPA, driven by well-intentioned investigators and companies striving for comprehensive programs, complexity has crept in, leading to less-than-ideal outcomes.

Several factors contribute to these poor outcomes:

1. Failure to differentiate between CAPA management and the CAPA execution process

Some companies treat CAPA as a mere set of standard operating procedures (SOPs) rather than a holistic system.

2. Lack of clear documentation

Inadequate descriptions of how different CAPA elements work together, define trigger events, and contribute to overall control can hinder understanding.

3. Insufficient knowledge and training

Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) may lack the necessary skills to document, investigate, analyze, and write clear CAPA documents.

4. Overcomplication

Trying to turn CAPA into something it’s not, such as Six Sigma/DMAIC, or failing to recognize it as a regulatory requirement can lead to confusion.

To understand a robust CAPA program’s complexity, imagine describing it solely through text-based SOPs.

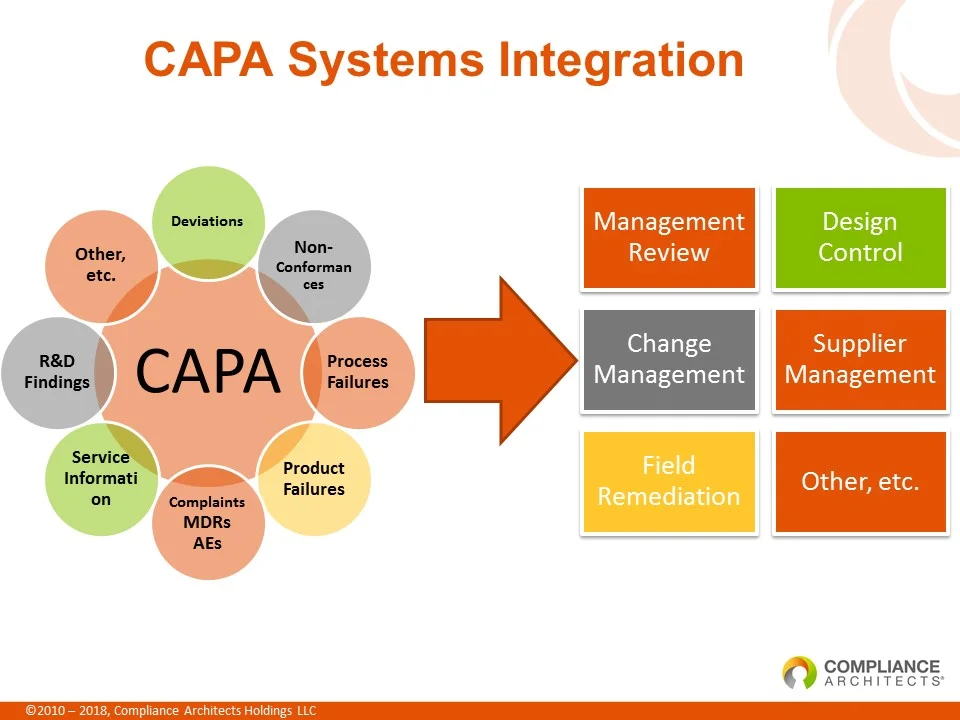

As the figure below illustrates, CAPA involves numerous interconnected elements, and conveying their relationships in written documents can be challenging.

This is where “The Untold Story” comes into play.

The Untold Story

What do we mean by “The Untold Story”? Simply put, it highlights the failure of many companies to effectively communicate in their quality and compliance documents, particularly in CAPA-related materials.

Many CAPA documents are, frankly, indecipherable. They are riddled with jargon, disjointed statements, proprietary acronyms, unsupported conclusions, unexplained data, and internal inconsistencies.

Moreover, companies often struggle to illustrate how the various sub-process elements of CAPA work together. This communication failure extends beyond CAPA documents and is a broader issue in FDA compliance activities—failure to communicate clearly and effectively.

So, what’s the solution for CAPA? It boils down to telling a good story or a series of related stories. Why stories? Because humans are hardwired for narratives.

We process information best when presented in story form, and that’s precisely why we create documents like CAPAs—to communicate effectively with regulators and other stakeholders.

To convey information to the FDA, we need to tell more stories. Our CAPA system and individual CAPAs should present a clear and coherent narrative. This approach has yielded positive results when working with clients. Stories simplify technical writing, making complex details more accessible.

An introductory story structure can be applied to CAPA, aligning it with the following elements:

| STORY STRUCTURE | CAPA STRUCTURE |

| Exposition: Character / Scene Development | Background and Details of Event/Incident |

| Conflict / Rising Action | Investigation |

| Crisis / Climax | Root Cause Analysis |

| Falling Action / Resolution | Corrective / Preventive Action |

Utilizing this structure, you can improve your technical writing for FDA compliance. While CAPA documents will still contain references to SOPs, technical details, and complex activities, framing them within a narrative structure makes them easier to understand.

This type of writing helps FDA investigators grasp your operation, demonstrates your SMEs’ comprehension of failure issues, and ultimately enhances your compliance outcomes.

In conclusion, CAPA is more than just a set of procedures; it’s a system that relies on compelling storytelling. By embracing this approach, companies can improve their CAPA programs and, in turn, their overall compliance with FDA regulations.

It would be best if you learned more about our Writing For Compliance Innovative solution to write better content that tells your organization’s untold story.

Elevate Your FDA Compliance Writing with Writing for Compliance®

Join us at Writing for Compliance®, a workshop designed exclusively for the FDA-regulated industry to improve writing skills and enhance regulatory inspection outcomes.

Proven Excellence

With a six-year track record serving FDA-regulated companies, Writing for Compliance® boasts impressive results:

- 95% found the workshop highly relevant to their roles.

- 94% would recommend it to their colleagues.

Key Program Areas

Our revamped program covers critical writing aspects for regulated industries:

- Discover the essential factors for success in FDA and regulatory inspections.

- Learn how to craft documents for regulators as the primary audience.

- Master the art of presenting data, statistics, and scientific information.

- Create documents that meet rigorous inspection standards.

Experience the synergy of compliance excellence and effective writing at Writing for Compliance®.

Click here to Elevate your compliance standards with Writing for Compliance® today!

Please contact us below for information on building sustainable FDA compliance with world-class CAPA programs for pharmaceutical, medical device, and other FDA-regulated companies.

Contact Form

FAQs Regarding CAPA

What does CAPA stand for?

CAPA stands for “Corrective and Preventive Actions.”

What is the ISO standard for CAPA?

The ISO standard for Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) is ISO 9001:2015. This standard outlines the requirements for a quality management system and includes guidelines for implementing effective CAPA processes to address nonconformities and prevent recurrence in various organizations.

Who initiates a CAPA?

A Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) is typically initiated by an organization’s internal quality management or compliance team. These teams monitor and assess processes, products, or services for deviations or nonconformities. When such issues are identified, the quality or compliance team initiates the CAPA process to address and rectify the problem, prevent its recurrence, and improve overall quality and compliance within the organization.

What are the four stages of CAPA?

The Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) process typically involves four main stages:

Identification: In this stage, the issue or nonconformity is identified through various means, such as internal audits, customer complaints, quality control inspections, or other monitoring processes. The goal is to pinpoint the problem and its root cause.

Investigation: Once the issue is identified, thorough research is conducted to determine the underlying causes and potential impact. This stage involves gathering data, analyzing information, and performing root cause analysis to understand why the issue occurred.

Correction: After understanding the root cause, corrective actions are implemented to address the immediate issue. These actions are designed to correct the problem at hand, prevent its recurrence in the short term, and mitigate any immediate risks or negative impacts.

Prevention: In the final stage, preventive actions are implemented to ensure that the issue does not recur in the future. This may involve process improvements, training, policy changes, or other measures to prevent similar problems from happening again. The effectiveness of these preventive actions is monitored to verify that the issue has been successfully stopped.

These four stages are essential for organizations to continually improve their processes, maintain quality standards, and ensure compliance with regulations and customer expectations.

What should a CAPA action plan include?

A concise CAPA action plan should include:

Problem Statement: Clearly define the issue.

Root Cause Analysis: Identify why it happened.

Corrective Actions: Outline immediate steps.

Responsibilities: Assign roles.

Timelines: Set deadlines.

Resources: Specify what’s needed.

Preventive Actions: Describe future prevention.

Verification: Explain how effectiveness is checked.

Monitoring: Detail ongoing oversight.

Documentation: Keep comprehensive records.

Review and Approval: Define the approval process.

Closure: Specify criteria for completion.

Follow-Up: Describe constant checks.

A streamlined plan ensures systematic issue resolution and process improvement.

What is the CAPA framework?

The CAPA framework is a structured approach organizations use to identify, address, and prevent quality problems or nonconformities in processes, products, or services. It typically involves the following key steps:

Identification: Identify and define the problem or nonconformity.

Investigation: Conduct thorough research to determine the root cause of the issue.

Correction: Implement immediate corrective actions to resolve the current situation.

Prevention: Develop and implement preventive measures to prevent the problem from recurring in the future.

Verification: Verify and validate the effectiveness of both corrective and preventive measures.

Monitoring: Continuously monitor and review the CAPA process to ensure long-term success.

The CAPA framework is widely used in quality management, compliance, and process improvement to enhance product quality, customer satisfaction, and organizational effectiveness. It helps organizations address issues systematically and prevent recurrence, leading to continuous improvement and better outcomes.

What is an example of CAPA quality?

In a manufacturing scenario, a CAPA quality example involves a company facing recurring malfunctions in electronic devices due to faulty components from a supplier:

Corrective Action:

Identification: Problem: Faulty parts.

Investigation: Cause: Supplier’s inadequate quality control.

Correction: Immediate actions: Replace faulty parts, recall and fix defective devices.

Preventive Action:

Prevention: Prevent recurrence: Strengthen supplier quality criteria, conduct rigorous audits, and improve communication.

Verification: Verify actions: Enhanced quality checks ongoing complaint tracking.

Monitoring: Continuous supplier quality monitoring and malfunction analysis.

Result: Improved product quality, fewer complaints, and prevention of future issues with faulty components.

What is the KPI in CAPA?

In CAPA (Corrective and Preventive Action), key performance indicators (KPIs) measure effectiveness:

Cycle Time: Time for CAPA completion.

CAPA Closure Rate: Percentage of closed cases.

Root Cause Analysis Accuracy: Correct identification rate.

Effectiveness Verification: Success of preventive actions.

Cost of Quality: Financial impact.

Customer Satisfaction: Reflects quality.

Recurring Issues: Instances of problem recurrence.

Regulatory Compliance: Adherence to rules.

CAPA Escalation Rate: Need for higher-level involvement.

Process Efficiency: Process optimization metrics.

KPIs guide improvement efforts and quality assurance.

What is a CAPA report?

A CAPA report, part of quality management, is a concise document summarizing:

Problem Description: Clear issue explanation.

Root Cause Analysis: Underlying causes investigation.

Corrective Actions: Immediate issue resolution.

Preventive Actions: Future problem prevention.

Responsibilities: Roles for each step.

Timelines: Set action deadlines.

Verification: Confirm effectiveness.

Monitoring: Ongoing progress tracking.

Documentation: Comprehensive records.

Review and Approval: Closing the CAPA report after successful completion.

CAPA reports help systematically address quality issues, maintain compliance, and serve as audit records.