FDA inspection risk management is an essential activity for regulatory compliance within pharmaceutical and medical device companies. While it is often challenging for medical product manufacturers to incorporate risk-based principles into their quality and compliance approaches, it is essential that compliance-implicated documents are drafted in a way that considers risk principles to facilitate FDA reviews during an inspection. Risk based principles are important because poorly written documents covering critical compliance topics can create one of the biggest risks a company might face during an FDA inspection.

Every development, commercialization and manufacturing process has risks – which FDA expects companies to mitigate. While the reduction of all risk to zero is unrealistic, the FDA expects that manufacturers bring risks down to acceptable levels. Similarly, the development of quality records presents its own set of risks. Every compliance document presented to investigators must be created with risk mitigation principles in mind.

Table of Contents

Quality Document Risk

While most quality organizations and professionals understand product and process risk considerations, what are the risks associated with documents themselves? Simply put, poorly written documents often fail to create an easy-to-understand story of how a company identifies, considers and manages risk. FDA investigators are not obligated to go out of their way to obtain additional information to clarify information or concepts they don’t understand in a document. Instead, they often will simply issue a 483 observation and be on their way. Enough bad documents, and one observation can lead to multiple observations, which in time, could lead to a warning letter if initial concerns are not comprehensively responded to and addressed.

What are Good Documents?

What constitutes a good document for the FDA’s inspection purposes? First and foremost, it must contain the information necessary to demonstrate compliance with regulatory requirements. Information conveyed must be based on sound technological and scientific principles. But it’s not enough for a company to believe — even to know — that its operations are scientifically sound and compliant with FDA requirements and expectations. If that information is not written clearly and in a way that is easy for investigators to understand, it may not withstand scrutiny during an inspection.

For FDA inspection success, it is critically important to understand that if a document does not clearly communicate compliant activities and adherence to SOPs, investigators are likely to have significant questions or concerns, and those issues will likely be reflected in 483 observations.

Obstacles to Developing Inspection-Ready Documents

There are many reasons why a company might find it difficult to ensure that its documents are well-written. Employees tasked with producing documents might lack skills and training to write well, or, may not have enough time to craft good documents. Training in writing principles and techniques are generally not included in training curricula for employees or may not be among the skills sought during the hiring process.

In many cases, companies may just not emphasize – or even understand – how critical good writing really is. There can be a tendency within the drug and device industries to consider scientific and technical competence as the most important contributing factor for successful outcomes of quality operations. This can lead to a lack of focus on the importance of writing for clear communication. Similarly, companies may fail to understand and convey the regulatory basis for written documents, not considering their purpose(s), structure and usability for both internal and external readers.

Identifying Problem Documents and Problem Writing

When determining which documents pose the greatest FDA inspection risk, companies must first look at which documents are most likely to be reviewed by the FDA during an inspection. Focus documents include quality, technical and problem-solving records. These are also, not coincidentally, the documents most likely to result in 483 observations. Further, technical records, such as validation protocols and reports, design records, and documents detailing complaint handling, deviations, non-conformances and CAPA, are among the highest-risk documents. The FDA may also ask to review SOPs, device history records, device master records and master batch records to check for consistency between these and the quality records memorializing the compliance activities.

The key to identifying — and then correcting — problem documents is to establish a system of ongoing document reviews where an internal person or consultant examines each compliance-implicated document in the same way the FDA would. If a given report does not meet expectations, the reviewer must identify exactly what is wrong — possibly listing questions that an investigator might have about the document — and make recommendations for improvement.

Document Organization and Structure — Essential to a Good Story

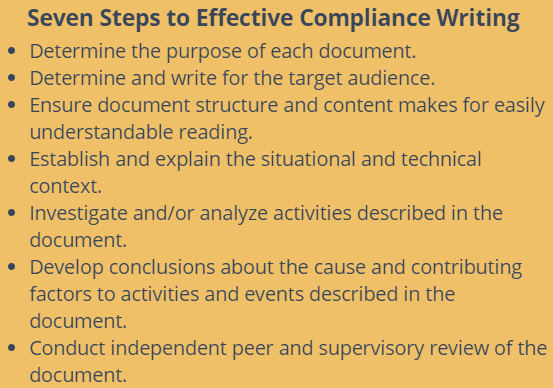

Document organization and structure — the third step in the Writing for Compliance® structured writing process (see sidebar above) — is critical to ensuring that investigators and others can easily follow the story being told in each document. An outline of required document sections, including one that lists names of all people involved in activities related to the record, is critical. The organization of content in the document should mirror the chronology of the activity, moving carefully from the beginning, through the middle, to the end of the story. An executive summary — written last — can give readers the gist of the document’s purpose and conclusions. A table of contents or content map can also be useful. Other key organizational points:

- Naming conventions need to be established;

- Acronyms and terms should be defined to ensure proper understanding;

- Determine where in the document peer and/or technical reviews are needed;

- Establish accurate, helpful and easy to follow references to all attachments, making sure attachments are easy to find and review; and

- Where electronic systems are used, companies need to ensure that these can produce readable, user-friendly printed documents.

The way in which a company organizes content within the structure of a regulatory document can also play a critical role in how easy is to follow and understand the story being told. Bold paragraph headings and frequent paragraph breaks, along with use of bullets to isolate important information can support this goal. Writing should be clear as to the relationships between cause-and-effect and problems and solutions. Finally, readability is improved when authors write in the third person and use an active voice.

Context: Key to Understanding and Comprehension

Underpinning easy to digest content within a regulatory document are the situational and technical contexts that establish foundational information for the entire document. This step of the Writing for Compliance® structured writing process provides the background necessary to understand the compliance story being told by the report in question.

To establish situational context, the company needs to describe the genesis of the event, activity or problem and, explain its significance. This is where the involved parties should be identified and the preliminary who, what, when, where and why are established. The document must explain what requirements and expectations were applicable and state the desired outcome. Technical context will explain the underlying engineering and scientific concepts and lay the foundation for considerations such as risk to the product or patient. Technical context helps to define significance in a compliance document, while linking that information to performance requirements and clinical or functional considerations. By thoroughly documenting situational and technical context, companies can apply risk-based principles to their writing process.

Other common document problems to watch for include:

- Failure to define the overall document purpose (discussed in Article 2 of this series);

- Failure to support the document purpose with appropriate content and information;

- Writing for science, for management, or for some reason other than compliance;

- Failure to adequately support content and information with facts/data;

- Too much or not enough detail;

- Including irrelevant information;

- Assuming too much audience knowledge;

- Over-use of jargon and/or acronyms; and

- Poorly structured sentences and paragraphs.

Well-structured documents incorporating risk-based principles help to reduce FDA inspection risk by ensuring that a manufacturer’s compliance story is clearly and thoroughly told. This allows the company to control the dialogue with the FDA. When an investigator begins asking questions about operations due to deficient writing that doesn’t effectively relate a company’s story, the FDA controls and directs the dialogue.

To summarize; well-structured, well-written documents lead investigators to the conclusions your company desires and makes them difficult to challenge. Conversely, poorly written documents can create incorrect conclusions that can lead to 483 observations — or worse — that will often require time-consuming (and possibly unnecessary) remediation actions to address.

In our final article in the series on Writing for Compliance®, we will discuss the importance of investigation and analysis; what is different between the two; and how to ensure you are developing well-reasoned conclusions from these critical activities. Stay tuned.

Writing for Compliance

Writing for Compliance® is the breakthrough workshop training that is FDA-regulated industry’s first and only formal training program devoted to improving FDA and regulatory inspection outcomes through improving writing skills within regulated companies.

The new Writing for Compliance® program covers a wide range of topics that are fundamental to writing for regulated industry purposes, including but not limited to:

- the one thing you must do to succeed in any FDA or other regulatory inspection;

- key principles of writing for regulators as a primary audience;

- representing data, statistics, and scientific information;

- focus on quality records and inspection-focus documents; and

- the incorporation of legal advocacy principles to maximize document effectiveness.

To learn more about Writing for Compliance click here.

Contact Us

To learn more about how quality records and documents create your biggest FDA inspection risk, fill out the form below.