Quality culture, a term that has been gaining traction in regulatory compliance, is taking center stage in the life sciences industry. In a recent webinar below, industry experts discussed the FDA’s growing interest in quality culture and its pivotal role in ensuring the success and safety of pharmaceutical and medical device products.

Before diving into the details, let’s take a moment to understand what quality culture means in this context. Quality culture refers to an organization’s collective behaviors, values, and attitudes that prioritize and promote product quality and regulatory compliance. It’s about fostering an environment where every decision and action aligns, intending to deliver safe and effective products to consumers.

The FDA’s Evolving Perspective

Opening the discussion, a seasoned industry professional emphasized how the FDA’s perspective on quality culture evolved over the past decade. They noted a significant increase in warning letters issued by the FDA that cited the lack of quality leadership and raised concerns about organizational culture related to quality.

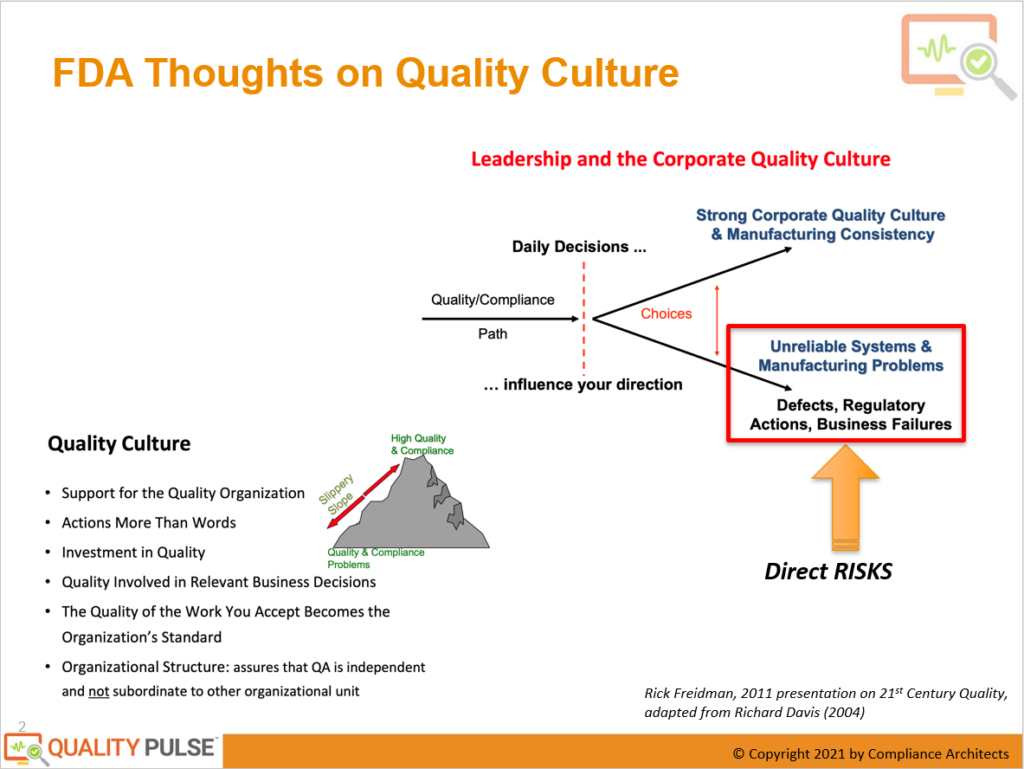

The linkage between leadership and corporate quality culture was underscored as essential. It was explained that every decision made within an organization, whether at a manufacturing facility, a corporate office, or a research and development department, impacts the overall quality compliance profile. This profile resembles an image slowly being formed pixel by pixel, with each daily decision contributing to its development.

The Impact of Daily Decisions on Quality Culture

Daily decisions can lead to two distinct outcomes within an organization. On the one hand, they can foster a robust quality culture that ensures consistency in manufacturing, smooth product development, and reliable clinical studies with minimal deviations. This outcome results in easy-to-understand and interpret products benefiting the organization and patients.

On the other hand, poor daily decisions can result in unreliable quality systems, chronic manufacturing problems, numerous deviations during clinical trials, defects, regulatory actions, and business failures. Financial struggles, inadequate case-fill rates, and product shortages can also plague organizations, with potentially life-threatening consequences for patients.

The FDA’s Expectations for a Good Quality Culture

The discussion then turned to what the FDA expects from firms with a good quality culture. Drawing from insights shared in a 2011 presentation on 21st-century quality, it was highlighted that the FDA looks for tangible support for quality organization, actions that speak louder than words, and investments in quality across people, processes, and IT tools.

Quality should be an integral part of relevant business decisions, including budget discussions aimed at improving quality and reliability in production. Furthermore, the quality of work accepted by an organization should become the standard, affecting not only FDA inspections but also products’ overall performance and safety.

The Role of Organizational Structure

The final piece of creating a quality culture puzzle discussed was the importance of organizational structure. To ensure the independence and effectiveness of quality assurance (QA), it should not be subordinate to other departments such as R&D, supply chain, or production. Quality must stand separate, with the authority and responsibilities needed to function independently and make decisions that prioritize product quality and safety.

Ready to transform your organization’s quality culture and drive excellence? Take action now and embark on a journey of improvement with Quality Pulse®!

Why Quality Pulse®?

Quality Pulse® is the industry’s FIRST FDA-regulated quality culture diagnostic.

Quality Pulse® is a scientific, research-based assessment adapted from industry experts with actionable intelligence for excellence. Explore data-driven insights to boost your organization’s quality culture!

Ready for Transformation? FILL OUT THE FORM and experience Quality Pulse®‘s interactive reporting and analytics firsthand.

Contact Form

"*" indicates required fields

Request more information and experience the power of data-driven insights. Elevate your quality culture today.

In conclusion, the FDA’s increasing emphasis on a solid quality culture is a significant development in the life sciences industry. Organizations that prioritize quality in their culture, decision-making processes, and organizational structure are better positioned to deliver safe and effective products while minimizing regulatory risks. A solid quality culture will remain critical to success as the industry evolves.

FAQs About Quality Culture

Quality culture refers to an organization’s collective behaviors, values, and attitudes that prioritize and promote product quality and regulatory compliance. It’s essential in the life sciences industry because it ensures that products like pharmaceuticals and medical devices meet high safety and efficacy standards, protecting patients and the organization’s reputation.

Over the last decade, the FDA has become increasingly interested in quality culture. They now pay closer attention to the leadership’s role in fostering a culture of quality and have issued more warning letters that cite quality leadership issues and organizational culture challenges.

Every decision an organization makes, from manufacturing to research and development, influences the overall quality compliance profile. These daily decisions can either strengthen the quality culture, leading to consistent processes and reliable clinical studies, or weaken it, resulting in manufacturing problems, deviations, and regulatory issues.

The FDA seeks tangible support for quality organization, actions prioritizing quality over mere slogans, and investments in people, processes, and IT tools. They also expect quality to be involved in relevant business decisions and for the quality of work to be accepted as the organizational standard.

Organizational structure plays a crucial role in quality culture. Quality assurance (QA) must be independent and not subordinate to other departments like R&D or production. This independence allows QA to prioritize quality and safety without conflicts of interest.

Organizations can promote a strong quality culture by emphasizing leadership’s commitment to quality, investing in employee training and resources, involving quality in decision-making processes, and ensuring that QA functions independently.

Establishing a robust quality culture can lead to unreliable systems, manufacturing problems, deviations during clinical trials, product defects, regulatory actions, and business failures. Product shortages and compromised patient safety are also possible outcomes.

While regulatory agencies like the FDA do not have specific guidelines on quality culture, they expect organizations to demonstrate a commitment to quality and regulatory compliance in all operations. Compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and other industry standards is essential.

Organizations can assess their quality culture through employee surveys, internal audits, and by monitoring key performance indicators related to quality and compliance. Regular reviews and external assessments can provide valuable insights into the organization’s quality culture.

Quality culture is an ongoing effort that requires continuous improvement and maintenance. It should be integrated into the organization’s values and daily operations, evolving and adapting to changing circumstances and regulatory requirements.